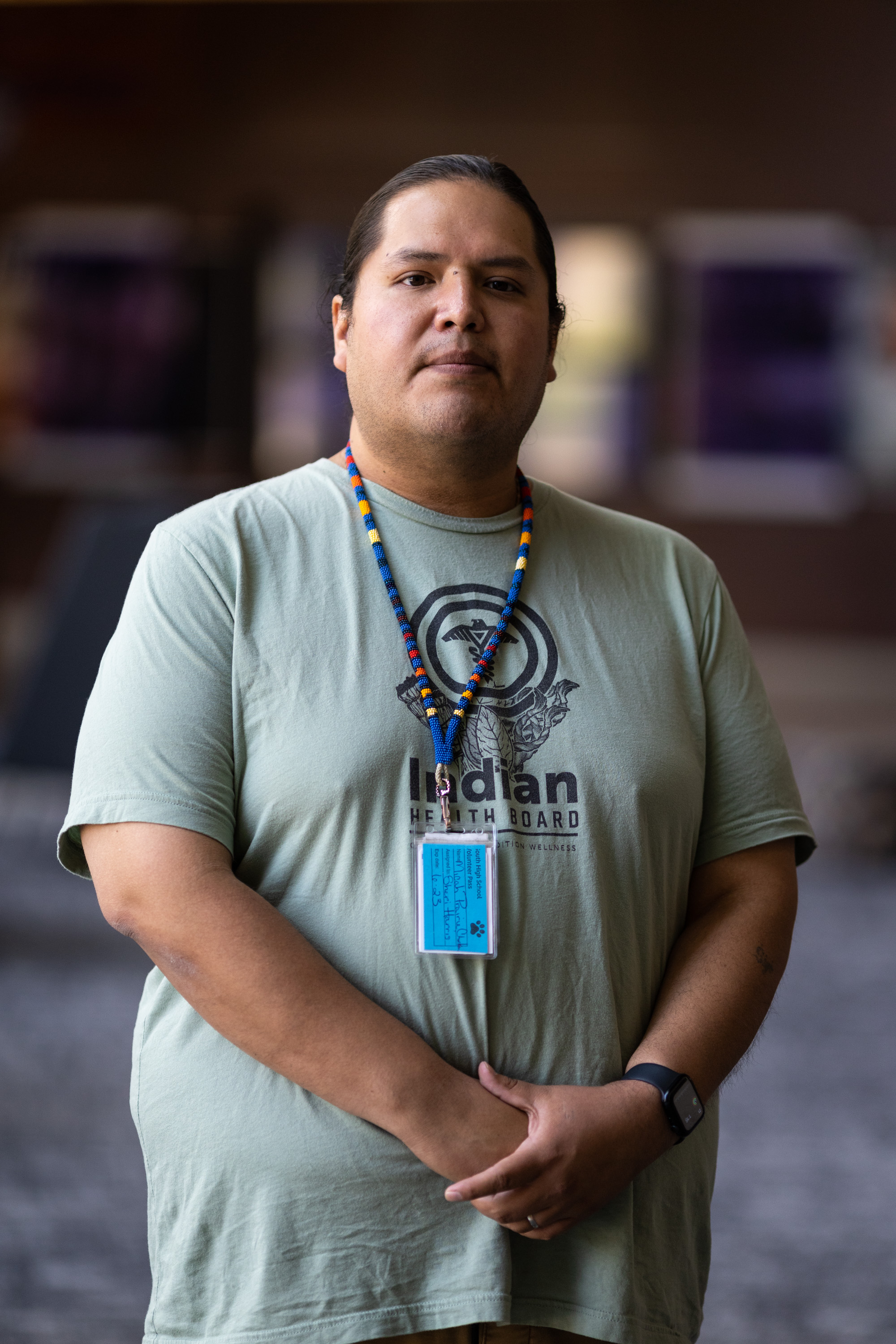

Since he was young, Dr. Micah Prairie Chicken has always wanted to help people. But as a clinician from an underrepresented community, he’s more of the exception than the rule.

“My dad was a licensed alcohol and drug counselor when I was growing up, so having a role model of that stature was a big influence on me,” said Prairie Chicken, a member of the Oglala Lakota and Mdewakanton tribes and postdoctoral fellow in clinical psychology at the Indian Health Board, a community health clinic near the Phillips neighborhood in Minneapolis.

Medical service to the Native community runs in his blood. But that doesn’t mean being one of a growing number of Indigenous people in health care in Minnesota has been easy.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in 2017 suicide was the second-leading cause of death for American Indian/Alaska Natives between the ages of 10 and 34, and Indigenous people report experiencing serious psychological distress 2 1/2 times more than the general population.

What’s more, the CDC reports that only about a third of Americans trust medical researchers to care about the public’s best interest. That distrust of the medical community is especially heightened among Black, Indigenous and communities of color.

According to the Association of American Medical Colleges, there are just over 2,580 doctors who identify as American Indian or Alaska Native, roughly one-tenth of 1% of the 1.07 million doctors in the country. There are more than 537,000 doctors who identify as white.

“When we are talking about [the] wellness of Native folks, we are talking about all aspects: physical, spiritual, mental, emotional,” Prairie Chicken said. “And I think that’s one thing that separates us from other health centers. We are not just a Western-based medical model.”

“Part of Native life is using all kinds of medicines that come from the land itself, so we use things like cedar grass, and we have our own garden where we grow all these traditional native plants,” he added.

As much as medicinal health is prioritized at the Indian Health Board, so is spiritual health. One way the clinic incorporates Native culture is by relying upon knowledge keepers, or elders who maintain the ancient history of their tribe.

Knowledge keepers have been able to learn or retain their tribal customs, traditions, teachings and practices, Prairie Chicken said. These elders hold a special place in Native American communities. “They provide spiritual guidance and are looked to for guidance in general,” he said.

More than one-fourth of Indigenous adults lack health insurance and more than half of Indigenous people rely on Indian health services, but due to underfunding, facilities tend to be crisis-driven and leave a wide gap in adequate and preventative health care for many Native Americans, according to Native American Aid, a South Dakota-based advocacy organization.

A sense of crisis also creates a sense of urgency, and the opportunity to step up. Like Prairie Chicken and his father before him, “a lot of Native mental health providers got into this line of work because of the call to help more people,” he said.

ThreeSixty Journalism students are passionate about mental health and how it impacts their community, which is why the stories produced at News Reporter Academy this summer are so important. In partnership with the Center for Prevention at Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Minnesota and led by MinnPost, students are profiling mental health resources in underrepresented communities. This resource guide highlights important people and organizations doing mental health work throughout the Twin Cities. Click to read more stories.

Indian Health Board Featured at TV Camp, Too!